What do Area-51, COVID-19 and 5G, QAnon, Who killed JFK?, the faked moon landing, Elvis is still alive, 911 is an inside job have in common? The common denominator is that each one of these topics sparked a lot of discussion: online, in person, over the dinner table, etc.

I am careful to use the label “conspiracy theary” since I would not like anyone to feel offended. Anyone has the right to have an opinion and that must be respected. Once I was told, “I don’t believe in conspiracy theories, I believe in conspiracies.” Whether or not you believe in any of this “stuff” (let’s call it that for now), the volume of this “stuff” has undoubtedly increased recently. For instance, some ideas are logical and some are very far fetched - Birds aren’t real or Australia is not real, for example. How did this happen? Have we spun out of control? Is there more to come?

After being subjected to a few of these beliefs, I began to read and review articles and some old text books. I engaged in light, basic, background “research.” I refer to “research” in this way because anyone today can claim to do “research.” This word is used far too frequently and often for inaccurate reasons such as scientific research. We’ll discuss this later. Because of this, I decided to first attempt to answer some of these questions for myself.

What helps conspiracy theories develop?

Q: Do conspiracies happen during times of crisis?

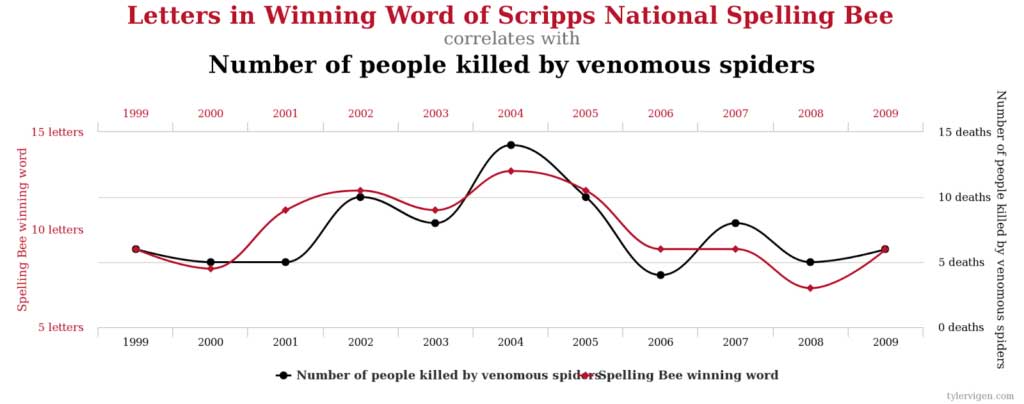

A: According to the articles reviewed, difficult times are historically a fertile ground for conspiracy theories to blossom. This is plausible - the more time of uneasiness and uncertainty, the more need for coping. This is an example of a strong positive correlation but keep in mind, correlation is NOT causation. I will revisit this later. So, let’s not claim anything unless it is scientifically proven via research.

Q: Could it be a simple way of coping?

A: It seems conspiracy beliefs are more than just a “simple way of coping”. People can engage in dangerous behaviors out of good intent. On 06/22/2017, according to the NPR article, a man based on the unfounded "Pizzagate" internet rumor accused Comet Ping Pong pizzeria of being the home of a Satanic child sex abuse ring allegedly involving many powerful individuals. He interrogated the staff and fired a weapon. In a letter to the court, the accused stated that he was "truly sorry for endangering the safety of any and all bystanders who were present that day." He claimed that he "came to D.C. with the intent of helping people." Often, by trying to do the right thing in the wrong way, it becomes the wrong deed.

Q: Why do some people believe in conspiracy theories and some do not?

A: Anyone can become susceptible to believing in conspiracy theories. These are elaborate, complex and logical ideas but often lacking in scientific evidence. What evidence exists is frequently taken out of context and findings can easily be overly simplified. Also, the scientific evidence needed to corroborate a belief may not be available at the time, so one must keep in mind that science takes time to verify the facts.

Let us elaborate on this further. A theorem is a result that can be proven to be true from a set of axioms (like a Pythagorean theorem). An axiom is a statement or a proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true. A theory is a set of ideas used to explain why something is true, or a set of rules on which a subject is based on. A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the natural world that can be repeatedly tested and verified in accordance with the scientific method by using accepted protocols of observation, measurement, and evaluation of results. Where possible, theories are tested under controlled conditions in an experiment. Scientific theories are created through the process of the scientific method. Observation and research lead to a hypothesis, which is then tested. Over time, a hypothesis can become a scientific theory if it continues to be supported by additional research.

Q: Are these ideas based out of fear and the need for stability?

A: Humans like certainty, and we look for solutions when we are faced with stressful situations or traumatic events. Having seemingly ‘simple’ answers help make us feel like we are in control and, therefore, less afraid of the unknowns.

Q: Do tribalism and social reasons have something to do with it?

A: Humans are tribal by nature and uniting around a common cause (and often against a particular group) may offer a sense of belonging and control. This often creates dichotomous thinking, or, polarized thinking, where things are either “black-or-white” — “all or nothing” – “you are with us or you are against us” — there is no middle ground. Strict polarized thinking places people or situations in “either/or” categories, with no shades of gray and no way to allow for the complexity of most people and most situations. A person with black-and-white thinking sees things only in extremes; however, many times the scientific research (especially in the social sciences) is ambiguous and unclear and must be repeated.

Q: Do people feel a sense of empowerment?

A: Knowledge is power. We all prefer feeling powerful rather than feeling powerless. When people ‘discover’ something outside of official, mainstream sources, they can feel powerful and knowledgeable, especially when they share these theories with others. This is gratifying to us, particularly when the complexity and uncertainly of life feels overwhelming. People who gravitate towards conspiracy theories can experience a seductive ego-boost. Strong believers can consider themselves part of the “unique and special” unlike the “uneducated and ‘naïve’ masses that do not know what is really going on”. (This is another example of dichotomous thinking.)

Q: Someone planned this on purpose type thinking?

A: This is called a fundamental contribution error. It is our tendency to prefer disposition explanations to situational ones. When we observe an event we are much more likely to attribute it to some intentional (in many cases malicious) internal motives than to circumstances and coincidences.

Q: Keeping the beliefs that confirm our idea and rejecting the ones that discredit it?

A: This is called confirmation bias. This is why people gravitate only to the resources that confirm their beliefs and prejudices. It is hard to challenge ourselves to change or accept something new (especially when we feel we have made an error). It is much easier to defend the original idea or mindset. Relating to research, it could be said that an academic is being biased towards his/her hypothesis causing a threat regarding internal validity.

Q: Do some people purposefully exclude a wide range of sources or opinions?

A: People may engage with conspiracy theories when the sources they are visiting are presenting these theories as facts. The truth may also be complex and unknown, and people may be unsure about which sources are trustworthy. This is becoming particularly problematic in recent history and present times as public mistrust with various suppliers of information continues to grow.

Q: Assembling a puzzle and pattern recognition?

A: For our safety, our brain has developed and evolved over time to recognize patterns, especially in dangerous environments. This can sometimes become overly developed - apophenia: a tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated matters.

The brain seeks order, cause and effect, and intention. A similar issue in research can be described as data dredging (also data fishing, data snooping, data butchery, and p-hacking). It is the misuse of data analysis to find patterns in data that can be presented as statistically significant, thus dramatically increasing or understating the risk of false positives. As mentioned before, correlation is NOT causation.

Q: Can theories be created out of political motivation?

A: This is called motivated or directional reasoning. In this case, people align themselves with conspiracy theories that help establish or back up their existing political or world views. An example of this would be supporting theories that make opposing political parties views look badly or supporting theories that make the opposing political party look responsible for a crisis.

Q: How about the desire for control and security of our lives or lack off?

A: We have a natural desire to have control of our lives. In fact, we do have control in many aspects of our lives while in other ways, for reasons beyond our control, we do not. Theorizing opposite facts can give the believers a sense of control and security. For example, global temperatures are rising and requiring of us all to make some level of sacrifice but if someone can explain how rising global temperatures is a hoax then we can more easily maintain our currant way of living without feeling guilty and without making any compromise.

Q: How about the desire for understanding and certainty?

A: We are constantly asking why things happen the way they do, especially when something happens to us directly. This can be a trap for our mind - control fallacy cognitive distortion. Control fallacy is a set of beliefs that has two options: 1) Everything is in my control; or, 2) Nothing is in my control. For example, if someone were to study for a test and fail, two sets of control fallacy statements could emerge. “It’s all my fault for getting sick and not studying enough” – this supports the idea that everything is in my control. Or, in the same scenario, “The teacher didn’t give me enough time to catch up and there were trick questions” – supporting nothing is in my control. Correspondingly, a conspiracy theory is set of beliefs. Sometimes our beliefs can be false; however, people often have acquired interest in maintaining the same set of beliefs.

What could be the dangers of conspiracy theories?

Q: Triggering conflict between people?

A: Conspiracy theories and similar beliefs can divide family members and affect friendships when lives become dominated by these beliefs. People are willing to defend them at the expense of their relationships with others.

Q: Increase in prejudices?

A: A person's upbringing may cause them to become prejudiced. If parents hold prejudices of their own, there is a chance that these opinions will be passed on to the next generation. One bad experience with a person from a particular group can cause a person to think of all people from that group in the same way. This is an example of generalization, an ego defensive strategy or, in a more severe form, overgeneralization - one of many cognitive distortions. Conspiracy theories tend to fan the flames with certain groups by solidifying already developed prejudice.

Q: Spreading fear and misinformation?

A: False or misleading information can have damaging consequences. Increased access to technology, as well as, access to social media across the globe (despite development level) allowed many people to have a microphone and a camera. Certainly, everyone does have a right to be entitled to their opinion. However, when the same opinion is not verified and when it poses a significant risk to public health it can quickly spread like wildfire and cause seriously damaging effects.

Q: Undermines Trust?

A: Conspiracy theories undermine trust in institutions like the World Health Organization (WHO) or the United Nations (UN), not to mention the media. Trust is one of the foundations of every relationship. Without trust, the relationship cannot survive. When conspiracy theories and similarly strong beliefs undermine trust, they then undermine the position or the authority of already established entities. It is very hard to acquire public trust and even more difficult to maintain it. Trust is like a container being filled with water. It is difficult to fill it, yet easy to empty it. It only takes a tiny hole to compromise the integrity of the entire container. Yet, identifying where the hole might be, repairing it and filling the container back up, takes time.

How to connect with others who may believe in conspiracy theories and how can we help ourselves?

- Acknowledge their feelings: As mentioned, a large part of engagement with conspiracy theories is driven by fear and lack of control. The best thing you can do to help others through difficult times is to actively listen and assure them that feeling scared or uncertain is completely normal.

- Not getting involved: It may be a good idea to change the conversation right from the get-go. This approach may be effective with someone with whom we are not very close. Some people may be deeply passionate about the topic and may be engaging in dichotomous thinking far too strongly. You may sense the “us versus them” type of attitude. In this case, one may genuinely try to change the topic while attempting to shift focus on something positive, perhaps benign, and less controversial. Simultaneously, we may model an appropriate response or overall attitude and be welcoming to the person but not necessarily their story.

- Challenge the argument (gently) but not the person: This approach could work with someone like a close family relative or a close friend. Find out as much as you can about what someone believes and have an open discussion with them. Ask questions, model fair and respectful debate and be sure that everyone gets space to talk. Being respectful and assertive is particularly important. It is important to keep the conversation balanced (not having anyone monopolize the conversation). Do not push. If you cannot agree, let it go for a while, and focus on building trust and respect. We can always “agree to disagree.” Stay as far away as you can from sarcasm, micro-aggressions, ridiculing, name calling, etc. Everyone has an innate desire to feel respected.

- Encourage critical thinking: Demonstrate the need to examine opinions and ideas and where they come from. Your goal should not be to stop people from talking about the things you do not approve of or to change their minds. Rather, the goal should be to expose people to different sources and perspectives. We need to be aware of our personal biases and acknowledge the same. Credibility and dependability are important.

- Reliable resources and a pragmatic attitude: Just because some things are logical, that does not make them necessarily true. A paradox is self-contradictory by definition. At times, we need to embrace ambiguity, confusion, lack of scientific knowledge and apply what we know in the appropriate context. Whenever we have an opportunity, we need to back up our discussion points with accurate, reliable, multi-cited facts. Facts are not opinions and the context must remain pragmatic. Guiding people to trusted and reputable sources can be hard because of the public’s general undermined trust (including in science which is often politicized). Almost anything can be interpreted as part of “the conspiracy” so do not expect people to be open to suggestions immediately. Keeping the conversation open is a great start to ongoing respectful debate.

Undoubtedly, many people across the world fell (and are continuing to fall) into this “rabbit hole” of beliefs. All these beliefs, however severe, incur a liability of some magnitude on our society. For instance, the "Flat Earth” type of belief might be severe and radical but is not likely to have a huge impact on society. On the contrary, a person/persons may possess a certain belief system that is so controversial and speculative, so radical and unsubstantiated, so lacking of scientific evidence yet, somehow, cause massive, global, and devastating consequences. I do not even want to identify a type of belief, since naming it may fan the flame and alienate people even further with whom I disagree. Again, everyone is entitled to their opinion. Opinions, however, can lead to actions. We may be able to explain people’s actions and behaviors that does not mean we can always excuse them.

To be fair and objective, we can all appreciate the fact that science wants to help but science is also to blame. Science is hard, complex, ambiguous and sometimes, not interesting. Scientific articles are often hard to read and comprehend. In addition, colleges and universities, at times, pressure academics to publish too much and too frequently. We can all certainly do better. We need to spark scientific interest in the general population and especially in children. In my humble opinion, we need more intense education (I am aware that I am bias since I was a General Education major at one point) and not solely in the sciences. Universal literacy and media literacy are important and, as a society, we need to foster progressive thinking, systematic questioning, innovation, and moral and ethical development. Blind trust, superstition and unquestionable loyalty based on authority, age, or tradition will not help us in our current dilemma.

Relevant definitions for a better understanding of the topic discussed.

Conspiracy - noun

noun: conspiracy; plural noun: conspiracies

- a secret plan by a group to do something unlawful or harmful.

- the action of plotting or conspiring.

- "they were cleared of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice"

Theory - noun

noun: theory; plural noun: theories

- a supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained.

- a set of principles on which the practice of an activity is based

- an idea used to account for a situation or justify a course of action

A scientific theory is not the end result of the scientific method; theories can be proven or rejected, just like a hypothesis. Theories can be improved or modified as more information is gathered so that the accuracy of the prediction becomes greater over time.

Research - the systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.

Similar words: investigation, experimentation, testing, exploration, analysis, fact-finding, examination, scrutiny, experiments, tests, inquiries, studies, analyses, work.

Scientific evidence - is evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis. Such evidence is expected to be empirical evidence and interpretable in accordance with scientific method.